JACAR Newsletter

JACAR Newsletter Number 43

March 27,2024

Documents Spotlight

The 1936 Winter Olympics and Skaters

In Japan, figure skating is one of the most popular winter sports. In 2023 (Fiscal year), too, Japanese athletes once again played active roles on the global stage between with the ISU Grand Prix of Figure Skating that began in October and the World Figure Skating Championships held in March.

This year 2024 marks the 100th anniversary of the 1st Winter Olympic Games that took place in 1924. Japanese involvement in figure and other skating competitions began in earnest around the 1929 founding of the Dai-Nippon Skating Competitions Federation (DNSCF; today’s Japan Skating Federation), and Japanese skaters made their Winter Olympics debut at the 3rd Games held in 1932.

The 4th Games held in 1936 that would be last Winter Olympics before World War II marked a major step forward in Japanese skating history, with figure skater Inada Etsuko putting in a brave effort, 500-meter event speed skater Ishihara Shōzō being the first Japanese to place highly, and Japan’s ice hockey team (organized by the DNSCF) making its debut. In this article, I want to use JACAR records to look back at what the 4th Winter Olympics were like and the activities of the skaters.

Through JACAR, you can learn about the Olympics through Japanese-language newspapers published in the Americas and around Asia in a digital collection provided by the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. First, using these overseas Japanese-language newspapers, let’s have a look at what the 4th Winter Olympics were like and their results.

The 4th Winter Olympics were held from February 6–16, 1936, at Garmisch-Partenkirchen in Germany then under Nazi rule. Japan to the Games sent 14 committee members and 34 athletes, with the latter participating in the three event categories of skiing (jumping, cross-country, and Nordic combined), skating (figure and speed), and ice hockey.

At the time, northern European countries like Norway boasted overwhelming strength in figure and speed skating, while Canada could be proud of the same in ice hockey. It was expected that it would be difficult for Japan to capture a medal. Furthermore, the journey from Mukden (present-day Shenyang)—where the Japanese skaters gathered together from their respective locations—to Berlin was a 10-day long trip with connections via the South Manchuria Railway and the Trans-Siberia Railroad. Consequently, they would be at a disadvantage in terms of conditioning, too. Regardless of such circumstances, from the Japanese-language newspapers we can get the sense that the skaters were determined to take on the challenge.

First, there was the brave effort put up by figure skater Inada Etsuko. Known in Japan today as a pioneer women’s figure skater, Inada was an elementary school student who at 12 years old had been the youngest skaters at the 4th Winter Olympics. She gained popularity at home, where she was known affectionately as, “Mame-senshu – Etchan” (the little bean Miss Etsu), and she was a focus of news reports even in American Japanese-language newspapers.

The month before the Olympics, Inada had entered the European Championships held in Berlin, placing 9th. She also appears to have become a topic of interest in Germany as well, with an article that appeared in the San Francisco-based Shin Sekai Asahi Shinbun noting, “Chief of the Luftwaffe High Command Hermann Göring`s wife was so impressed that after the event she jumped into the rink and shook hands firmly with Miss Etsuko (Ref. J21022089000). The paper even drew on a comparison with a famous American film star of the day to highlight her popularity, saying that at the Opening Ceremony:

“Inada Etsuko was praised like she was in dreamland, and her popularity greater than that of Shirley Temple overwhelmed the whole of Europe. Miss Inada went into Berlin wearing a crimson dress . . . The mysterious Japanese red doll . . . was immensely popular” (Ref. J21022091100).

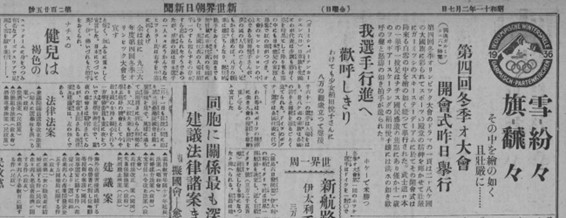

In the event itself, the Norwegian Sonja Henie won her third straight gold medal, while Inada placed 10th in a field of 26. Olympic participants sang praises of Inada’s brave effort, praising her as “someone who will likely reach the point in the near future where she will put on a wonderful performance that will best Miss Henie’s” (Ref. J21022093000).

Next we turn to the high placing posted by Ishihara Shōzō in the 500-meter speed skating event. In this event, too, Norwegian skaters took the top two places, while Waseda University’s Ishihara posted a new Japanese record of 44.1 seconds, sufficient to place 4th a scant 0.1 second behind the American 3rd place finisher (see Image 2). This was an outstanding achievement, marking the first time a Japanese athlete won a top-eight diploma in the Winter Olympics.

Ishihara was already 10th ranked in the world in his field. How do you suppose he acquired that excellence? Noteworthy here is the fact that Ishihara was originally from Andong (present-day Dandong in Liaoning Province) in colonial Manchuria.

The history of skating competitions in Japan cannot be told without mentioning colonial Manchuria. The Dairen-based Manshū Nichinichi Shinbun (not available through JACAR) once published a feature article about skaters; viewing this profile, one notes how many of them—other than figure skaters—came from Manchuria (see Image 3).

In fact, Manchuria’s strength in skating competitions outweighed that of the home territories. This was both because skating very much a part of local character in Manchuria—so much so that it was known throughout Japan “the Skater Kingdom Manchuria”—and because Manchuria was the first to adopt Western techniques with the support of the South Manchuria Railway (referred to in Japanese as “Mantetsu” for short).

With respect to speed skating in particular, through the good offices of Mantetsu, a Russian skater named “Rushichai” (Japanese transliteration, original not recorded) living in Harbin was invited to be coach. The Japanese skaters in Manchuria studied techniques with him. In 1931, Ishihara and two other skaters took part in the World Speed Skating Championships in Helsinki with Okabe Heita as manager, and they began to accumulate experience in international competitions. The source of Ishihara’s strength lay in the existence of this “Skater Kingdom Manchuria.”

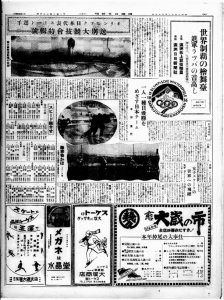

Finally, we come to ice hockey, an event in which Japan entered for the first time at this Winter Olympics. Japan played against Sweden and Great Britain. It lost both games and did not advance to the finals (see Image 4). The finals were won by Great Britain, which defeated the seemingly invincible Team Canada.

Manchuria again played a leading role when it came to ice hockey for Japan. Five of the 13 players on Team Japan were from Manchuria Medical University (MMU), and Shōji Toshihiko also of MMU served as team captain. MMU was a leader in speed skating. It made the decision in 1929 to send a squad to Europe, and it had the strongest team at the Japan national championships held in 1931. However, even with members from MMU on board, Japan’s national team still found the walls of the world to be thick ones.

That said, there is a deeply interesting fact to take note of when it comes to the national ice hockey team. Just before the Olympics, the team had taken part in a succession of contests due to an invitation it had received from a number of European countries. The records from that time can be found in the sports-related collection at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ Diplomatic Archives.

According to these documents, Romania’s Telefon Club Roman—serving as coordinator for several countries—sent a request to the Japanese embassy in that country for Japan’s national team to take part in a series of invitationals (see Image 5). The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in turn passed it along to the DNSCF, and scheduling arrangements were made.

As a result, the Japanese national team took the Trans-Siberia Railroad to Poland. After arriving, they played games on January 11 and 12, 1936, against the Polish team Krynickie Towarzystwo Hokejowe from Krynica-Zdrój. They then moved on, arriving in Berlin on the 15th, then went on to play in Prague on the 16th and 17th, Budapest on the 19th, Bucharest on the 21st, and Vienna on the 23rd and 24th before arriving in Garmisch-Partenkirchen on the 26th.

All told, the national team played eight games in five cities: Krynica-Zdrój, Prague, Budapest, Bucharest, and Vienna. With the Opening Ceremony for the Olympics taking place on February 6, they wound up having an arduous schedule. Years later, in fact, team captain Shōji recalled, “Everyone was exhausted when we got to Garmisch-Partenkirchen for the main event” (from Shōji Toshihiko, “Watashi to aisu hokkē,” Nihon Sukēto-shi).

However, they also received happy news after the invitationals. It was a fan letter from a Romanian that had arrived at the Foreign Ministry (see Image 6). The writer said the Japanese team’s skills were at a high level, and they admired the team’s enthusiastic attitude. Accordingly, they wanted to know the addresses of the team’s members so they could get the members’ autographs. It was perhaps someone who had seen the national team’s game with Telefon Club Roman. The Japanese national team was defeated in the Olympics’ preliminaries, but their all-out effort created a sensation among those who watched them play.

This completes our look at the 4th Winter Olympics and what Japan’s skaters were up to. The 25th Winter Olympics will take place in 2026 in Milan and Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy. When you watch the skating events, you might also give a thought back to the young athletes who bravely took on the world at the dawn of skating in Japan, and to “the Skater Kingdom Manchuria” that laid the foundations for Japan’s participation in skating competitions today.

Literature Cited

Hori Tadao, et al., eds. Nihon sukēto-shi. Nihon Sukēto-shi Kankōkai, 1975.

Japan Skating Federation, ed. Nihon no sukēto hattatsu-shi: Supīdo, figyua, aisu hokkē. Bēsubōru Magajin-sha, 1981.

Japanese Olympic Committee, ed. Kindai Orinpikku 100-nen no ayumi. Bēsubōru Magajin-sha, 1994.

Takashima Kō. “Manshū supōtsu shiwa (I), Memoirs of the Faculty of Letters, Kyoto University no. 60, 2021.

Takashima Kō. “Manshū supōtsu shiwa (II), Memoirs of the Faculty of Letters, Kyoto University no. 61, 2021.

Japanese Olympic Committee website, <https://www.joc.or.jp/column/olympic/winterhistory/0101.html>, last accessed March 25, 2024.

MATSUURA Akiko, Researcher, Japan Center for Asian Historical Records