JACAR Newsletter

JACAR Newsletter Number 41

September 30,2023

Documents Spotlight

A Century Since It Happened: The Great Kantō Earthquake and Diplomacy

Introduction

September 1, 2023 will mark a century since the Great Kantō Earthquake occurred. To memorialize the event, the Japan Center for Asian Historical Records (JACAR) will be holding two special internet-based exhibitions— “Did You Know This? Modern Japan Had This Kind of History” (featuring a section called, “Rebuilding the Imperial Capital: Recovery from the Great Kantō Earthquake”) and “Special Feature: Disaster and Recovery—Public Records from the Meiji, Taishō, and Shōwa Periods”—that introduce materials related to the Great Kantō Earthquake and other such natural disasters. In this article, I will take up some matters that have not been addressed in previous JACAR internet exhibitions on the topic—namely, how Japan got word to the outside world about the earthquake and what measures it took in response to the support that came from overseas.

1.Informing the Outside World about the Disaster and Support from Abroad

At 11:58 a.m. on September 1, 1923, a magnitude 7.9 earthquake with an epicenter in the northwestern part of Sagami Bay struck the Kantō region. The earthquake left as many as 370,000 houses partially or completely destroyed, wiped out, swept away, or buried, while the number of dead or missing would amount to approximately 105,000.

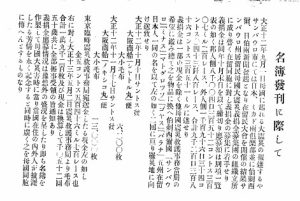

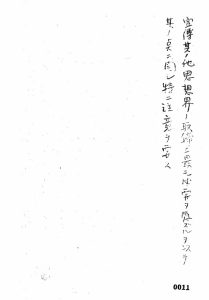

The following day, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) used naval wireless communications to send a telegram about the disaster to Japan’s ambassadors to the United Kingdom, the United States, and France, and its consul in Singapore. The telegram read in part, “In Tokyo, while the areas around the Imperial Palace and Yamanote were unscathed, around two-thirds of the city has been leveled. The British, American, French, Italian, and Chinese embassies were destroyed by fire. The Yokohama and Kamakura areas appear to have been severely damaged. Government striving to undertake emergency measures to deal with what it’s facing.” From this, one can sense the chaos in the earthquake’s immediate aftermath. (Image 1) After this, MOFA would go on to transmit updates to its foreign missions about the earthquake labeled as “general information.”

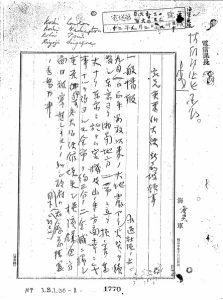

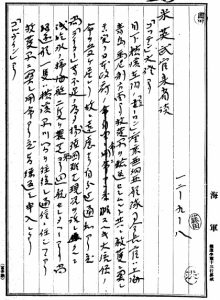

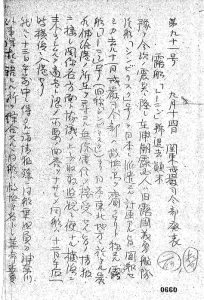

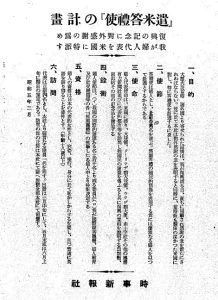

MOFA also sent out information regarding the whereabouts of diplomatic officials in the disaster-afflicted areas. An appendix titled “Earthquake and Fire Disaster and This Ministry” to issue 45 of the “Ministry of Foreign Affairs Bulletin” published October 15 contained information about earthquake damage to MOFA buildings as well updates regarding the whereabouts of foreign diplomatic officials and the state of damage to foreign missions. From materials available through JACAR, we can see that there were severe losses. Many embassies including those of the United States and France were burned to the ground, and in Yokohama the U.S. consul and the Brazilian consul general both lost their lives.(Image 2)

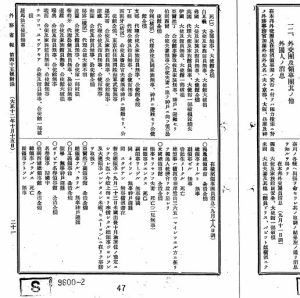

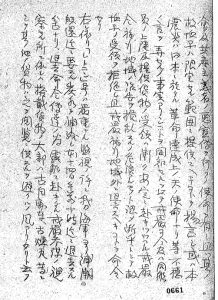

The first news of the disaster was issued the day of the earthquake on September 1 by wireless from a vessel offshore from Yokohama Harbor. The transmission was picked up by the Iwaki Wireless Telegraph Station in Fukushima Prefecture and dispatched to San Francisco and elsewhere. Through this, news that the disaster had occurred in an instant spread around the world, and a succession of relief supplies from various countries arrived in Japan. Particularly prominent was the support from the United States. Having received the initial report, US President Calvin Coolidge ordered Navy ships that had been deployed in the Far East to provide aid to the disaster victims. On September 5, the destroyer USS Stewart arrived in Yokohama. This was followed on the 10th by the arrival in Shinagawa of the USS Black Hawk loaded with such relief supplies as rice, sugar, and miso (see Image 3).

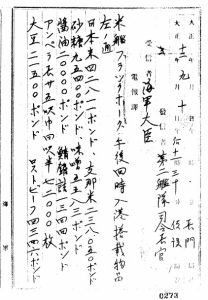

There was also a tremendous amount of aid from Japanese who were living overseas. We see from the “Register of Applicants to Donate Money for the Great Earthquake in the Mother Country” (Bokoku dai-shinsai gienkin ōbosha meibo) published by a group (Bokoku dai-shinsai gienkin ōbo shūdan) formed for that purpose put together by residents of São Paolo, Brazil, that donations came not only from Japanese living in that country but also Brazilians and persons of other nationalities as well. The records also show that some of the donations were used to buy relief supplies that were sent to Japan, such as the nearly 20,000 blankets of all sizes that were sent in October and November, 1923 (see Image 4).

The details about the donations and relief supplies from the various countries sent in response to the disaster were recorded in “Gaikoku gienkinpin ichiranhyō” (List of Donations from Foreign Countries) created by the Foreign Ministry’s Bureau of Commerce in April 1924. To take the relief supplies sent by the American Red Cross as an example, the records show that on September 19, 1923, the USS Vega out of San Francisco delivered 84,766 bags of rice, 65 tons of sugar, 765 tons of flour, and other goods to Japan (see Image 5).

2.Japan’s Initial Responses to Foreign Aid

There were a variety of problems in Japan’s initial response to the aid from these countries. In the wake of the USS Stewart’s arrival in Yokohama on September 5, one relief ship after another dispatched from other countries came to Japan. However, the port facilities were damaged, and offloading the supplies was difficult. Aware that Japan did not have enough carrying vessels, the US proposed that it urgently dispatch a minesweeper docked in Zhifu, Shandong Province, China, to be use as a carrier ship.(see Image 6)

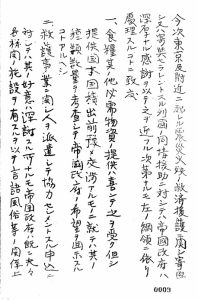

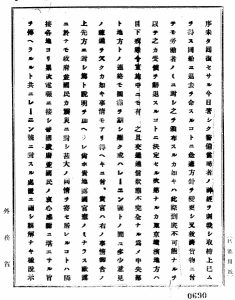

Pressured to settle on a policy for accepting aid from abroad, on September 11 the Cabinet settled on a three-point policy for dealing with foreign countries’ disaster relief activities (see Image 7).

(1) Japan would accept offers of necessary goods such as foodstuffs, but if discussions were held prior to departure it might also indicate its desired conditions.

(2) Japan would decline offers of aid workers and transport ships out of concern over “talk and rumors” (gengo fūsetsu nado).

(3) For public safety reasons, Japan would conduct inspections regarding ship’s personnel coming ashore and cargo offloading.

With regard to item 3 in particular, it was noted that care was needed with regard to propaganda about revolutionary ideas from the Soviet Union. It was done bearing in mind that Soviet vessels would dock in Japan.

Following the collapse of Imperial Russia in 1917, official relations between Japan and the Soviet Union would remain severed until Soviet-Japanese Basic Convention of 1925. However, after the disaster, among the relief ships sent to Japan was one that came from the Soviet Union. On September 12, the steamship Lenin arrived in Yokohama bearing doctors, nurses, and medical supplies. However, the following day it was ordered to leave the country by the Kantō Martial Law Headquarters. The reason for the expulsion was that Martial Law Headquarters had received information that the personnel aboard the Lenin had orders to propagandize to revolutionary committee members and communists, they had plans to distribute relief supplies only to certain persons (workers), and disturbing statements had been made that the earthquake was a heavenly command to accomplish revolution in Japan (see Image 8). The negotiations over the expulsion notice took place aboard the Lenin were led by the Martial Law Headquarters, and after being supplied with coal and water the vessel departed Yokohama on the 14th.

Following up on the Lenin’s expulsion, communicating through Deputy Consul General Watanabe in Vladivostok, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs expressed thanks to the Soviets for having dispatched the relief ship. However, it went on, the Japanese government was not able to fully express its gratitude owing to martial law having been imposed and the faulty transportation and communications situation, and it asked for the Soviet government’s understanding (see Image 9).

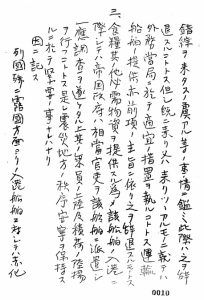

Furthermore, on September 18, concerned about any worsening of the situation between Japan and Russia in the future, the Cabinet settled on the following policy with regard to receiving relief from the Soviet Union down the road (see Image 10).

(1) Japan would accept relief supplies from the Soviet Union if their distribution was left solely in the hands of the Japanese government.

(2) As to the transport of supplies, Soviet vessels would be declined entry to Japanese ports. Instead, the government suggested the possibility that the Vladivostok consulate could receive those supplies and transport them via regular boat service from Japan.

After the Lenin’s expulsion, the Soviet government’s efforts to send relief supplies for all intents and purposes were brought to an end, as can be seen in the cancellation of plans to dispatch from Shanghai the Tomsk, which had been loaded with aid. However, the Soviet government left such disaster relief measures as exempting exports to Japan from customs duties and exempting relief supplies from freight charges in place.

3. Japan-US Relations in Disaster Recovery

A milestone for disaster recovery was marked seven years after the earthquake in 1930, when a celebration was held in March to mark the conclusion of reconstruction of the imperial capital, followed by completion that September of the Earthquake Memorial Hall (present-day Tokyo Metropolitan Memorial Hall). In February that same year, Jiji Shinpōsha announced plans to send a group of women as “envoys of gratitude to the U.S.” As representatives of the Japanese people, they were to express their gratitude for the sympathy and support received from the American people at the time of the earthquake, and also report on the state of recovery in Tokyo and Yokohama (see Image 11). The members of the committee that selected these women included Foreign Minister Shidehara Kijūrō, Recovery Bureau Director Nakagawa Nozomu, Tokyo Mayor Horikiri Zenjirō, and Yokohama Mayor Ariyoshi Chūichi. In making their selections, Foreign Minister Shidehara said, “I pray that these refined lady envoys will carry out their mission in a manner that leaves a memory that will be a delightful one in diplomatic relations between Japan and the United States” (see Image 12).

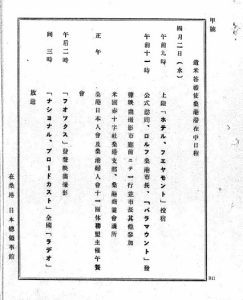

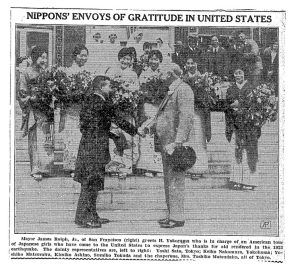

After observing the state of recovery in Tokyo and Yokohama, the envoys departed the latter city on March 18. From there, they traveled around the US making stops in Honolulu, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Washington, DC, Philadelphia, New York, Boston, Chicago, Seattle, and Portland. They returned to Japan on June 2. During their April 2–6 stay in San Francisco, the envoys visited the Chamber of Commerce and the Red Cross, among other sites (see Image 13). The welcome they received from Mayor James Rolph Jr. was also covered in the newspapers (see Image 14). San Francisco Deputy Consul General Kaneko spoke highly of the envoys’ visit, saying, “The sponsor’s plan to promote friendly relations between the two countries has created good will among the Americans, and the envoys have left a good impression everywhere” (see Image 15). Consuls in Los Angeles and Seattle had similar assessments. Furthermore, given Ambassador Debuchi’s report that “the President and his wife were extremely pleased to meet them,” the envoys played a definite role in friendly ties between Japan and the US.

*In the photo, Yokoyama Hidesaburō (l) (Jiji Shinpōsha), who was in charge of the girls on their tour, shakes hands with Mayor James Rolph Jr. (r)

Conclusion

In this article, I have introduced the connections between Japan and other countries in a time of disaster and the issues involved, doing so through the communications made by the Foreign Ministry, the aid received from various countries, the measures the Japanese government took in response, and Japan-US relations in connection with recovery. I hope that through this report, the reader will get a real sense of the ways in which Japan was connected to the international community on the occasion of this great disaster of the past.

*Information such as figures recorded in the materials was current as of the time that those materials were created. The information may be different from that presented in other materials as well as various records and research currently being presented.

Literature Cited

Iimori Akiko. “Taishō-ki Nihon gaikō no kyōchō to tairitsu: Shikōsakugo suru Taishō-ki kokusai kyōchō rosen” (Doctoral dissertation, Graduate School of Human Sciences, Tokiwa University, 2000).

Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Diplomatic Archives. “Kikaku-tenji ‘Daishinsai to gaikō: Kantō daishinsai to Meiji-Shōwa Sanriku jishin’ ni tsuite.” In Gaikō Shiryōkanpō (Journal of the Diplomatic Archives), vol. 26. 2012.

Okamoto Takiko. “Kantō daishinsai no gienkin shobun to Yokufūkai no sōsetsu.” Meiji Gakuin Daigaku Shakaigaku/Shakaifukushigaku kenkyū, vol. 146. Meiji Gakuin Daigaku Shakaigakubu, March 2016.

Shibusawa Eiichi Memorial Foundation, Shibusawa Memorial Museum. Shibusawa Eiichi to Kantō daishinsai: Fukkō e no manazashi. 2013.

Tsuchida Hiroshige. Saigai no Nihonkindaishi: Daikyousaku, Hūsuigai, Hunka, Kantō daishinsai to Kokusaikankei. Chuoukouronshinsho, 2023.

MIZOI Satoshi, Assistant Researcher, Japan Center for Asian Historical Records