Top Page > Homeland and Overseas, as Seen in Archival Records > Article 1: The Civilian Air Transportation Network that Linked Japan with Its Colonies

Article 1: The Civilian Air Transportation Network that Linked Japan with Its Colonies

1. The Growth of the Civilian Aviation Network

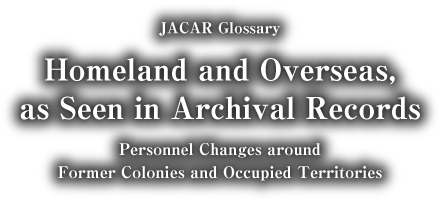

Image 1: “Map of Air Routes between Japan, Manchuria, and China” dating to 1939

(Aviation Bureau at the Ministry of Communications, ed., Kōkūyōran Showa 14 nenban [General survey of aviation in 1939], 1940)

The 1920s and 1930s saw a dramatic expansion in the size of the civilian aviation network.

The countries of Europe competed with one another to provide considerable support toward the development civilian aviation with ulterior motives about the possibilities it could mobilized in an emergency for military purposes. To counter this state of affairs, the Japanese government likewise worked to expand the network in its own country and territories.

The first air routes connecting Japan with its colonies began service at the end of the 1920s. The following decade saw this network linking the home country with Korea, Taiwan, Manchuria, and elsewhere grow at a fever pitch (see Image 1).

2. The First Regular International Service

The first regular international service between the Japanese mainland and its colonies was a Fukuoka-Ulsan-Gyeongseong (present-day Seoul)-Pyongyang-Dalian route that Japan Air Transport Corporation (JAT) began flying in September 1929.

JAT was Japan’s national flag carrier and charged with handling the country’s civil aviation business. It already had a Tokyo-Osaka-Fukuoka route, so by connecting to this new flight a passenger setting out from Tokyo could reach Dalian by the following day.

Aircraft operated by JAT included the Fokker F.VII (2 crew, 8 passengers) from the Dutch manufacturer of the same name, and the Fokker Super Universal (2 crew, 6 passengers) produced in the U.S. by Fokker-America. Fare for the flight from Fukuoka to Kyongang was 40 yen, as was the charge for the Gyeongseong-Dalian leg.

-

Image 2-1: Fokker F.VII passenger airplane

(File name: “Climate at Airfields and on Air Travel Routes; Civilian Aviation Routes; Domestic Travel; Item Regarding Japan Air Transport Corporation Aviation Routes; Item Regarding Flight Clearance Requests” [image 8] Ref:C04021869800) -

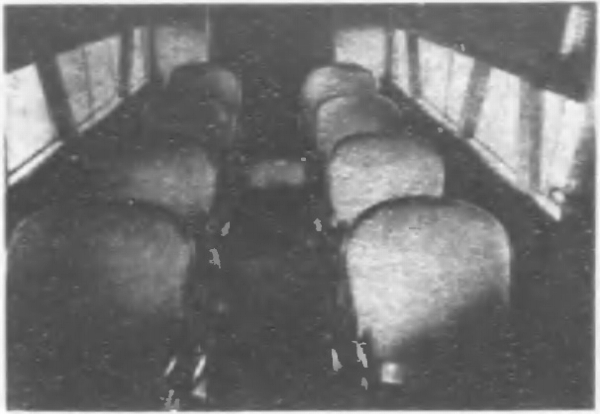

Image 2-2: Passenger cabin of the Fokker F.VII

(ibid. [image 9], Ref:C04021869800)

According to Ryotei to hiyō gaisan [Itineraries and cost estimates] (1930) produced by the Japan Tourist Bureau (ancestor to today’s JTB Group), sailing from Kobe to Dalian would take 4 days by passenger ship (arriving three days after departure). Ticket costs would have been 65 yen for first class, 45 yen for second class, and 19 yen for third class.

Ryotei to hiyō gaisan was one of the leading traveler’s guide books in Japan during the interwar period. It provided model travel routes and estimated costs, and was revised nearly every year. However, the 1930 edition did not include any information about air routes.

The guide book started to include air routes alongside their maritime counterparts in 1932.

Airplanes already had an advantage in 1929 when regular Fukuoka-Dalian service began in terms of the time a journey would require. However, their safety was an issue of tremendous concern, and airplanes had yet to demonstrate that they were a more practical mode of transport than ships.

3. To Manchuria, Taiwan, and the South Pacific

In September 1932, the Manchuria Aviation Company was founded under the protective guidance of the Kwantung Army. The new company began regular operations that November.

Initial routes included one that flew from Sinuiju to Mukden (present-day Shenyang), Hsinking (Changchun), Harbin, and on to Tsitsihar (Qiqihar). By connecting with a JAT flight at Sinuiju, a passenger traveling from the Japanese mainland could get to Manchuria the following day.

In October 1935, JAT began service on a Fukuoka-Naha-Taipei route, allowing someone who departed Fukuoka on a given morning to reach Taipei later that same day. (For details, please see “Kūkan Dai-1116-gō 10.10.4 Item Regarding Air Service between the Japanese Mainland and Taiwan” [C05034292500].)

Furthermore, in April 1939 Imperial Japanese Airways (IJA) began regular, twice-monthly service on a Yokohama-Saipan-Palau route.

IJA was Japan’s national airline, established in December 1938 through the consolidation of all civilian air transport companies.

According to a timetable from the time of the airline’s founding, a traveler departing Yokohama on a Tuesday morning would arrive in Saipan that same day. They could then take a flight departing Saipan that Thursday and arrive in Palau that same day. (For details, please see “Item Regarding Regular Tokyo-Palau Flights” [C01007343400].)

4. Government Agencies Overseeing Aviation in the Colonies

Air transport in the Japanese mainland was the bailiwick of the Aviation Bureau at the Ministry of Communications. Meanwhile, in Japan’s colonies it came under the control of various respective local colonial authorities: the Communications Bureau, Governor-General of Korea (with authority transferred in 1943 to the Air Transport Section, Transportation Bureau); the Communications Department, Transportation Bureau, Governor-General of Taiwan; the Manchukuo Transportation Department; the Communication Bureau, Kwantung Communication Authority; and the Transportation Section, Reclamation Department, South Seas Agency (with authority transferred in 1942 to the Transportation Section, Transportation Department).

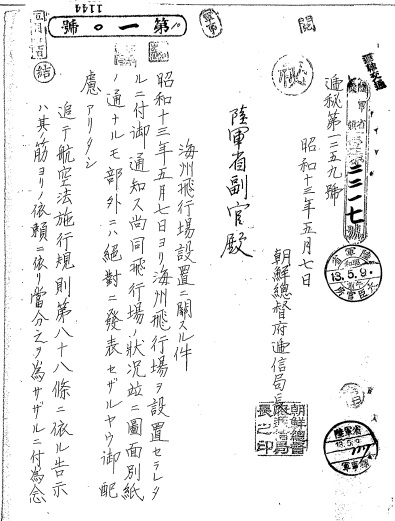

Image 3: File name: “Item Regarding the Positioning of Haeju Airfield” (image 1) (Ref: C01007118400)

Information about the various authorities in Japan and its colonies along with their areas of jurisdiction can be ascertained from a dispatch sent in May 1938 by the Communications Bureau of the Governor-General of Korea titled “Item Regarding the Positioning of Haeju Airfield” (Ref: C01007118400).

In it, the Bureau sent information about conditions at this then-newly constructed airfield in the western part of the Korean Peninsula along with a diagram of the site to the relevant authorities.

The Bureau asks that the dispatch’s contents be kept absolutely secret from anyone outside unconnected with the recipient departments, and includes a cautionary note to the effect that no announcements should be made to the general public regarding the airfield in question.

The document also includes a list of its recipients, presented by their titles. They include an Army Ministry adjutant, the chief of the Navy Air Service Headquarters, and the president of JAT, along with the director-general of the Aviation Bureau, Ministry of Communications; director of the Communication Bureau, Kwantung Communication Authority; chief of the Communications Department, Transportation Bureau, Governor-General of Taiwan; and chief of the Routing Office, Manchukuo Transportation Department.

From this document, we can get a sense of the various aviation authorities worked with one another while handling the civil aviation network.

5. Personnel Movements Between Japan and the Colonies

Personnel also moved back and forth among the various aviation authorities.

By way of example, consider the case of Matsuo Shizuma (1903-1972), who after the war served as director-general of the Air Transport Agency and later as president of Japan Air Lines.

Matsuo was a graduate of the Faculty of Engineering at Kyushu Imperial University. He joined the Ministry of Communications in 1930 after spending some time at a private-sector company.

At the Ministry, he worked in the Aviation Bureau, but soon was ordered reassigned to the Communications Bureau of the Governor-General of Korea.

Matsuo recollected after the war that he went in response to a request from the Governor-General because they did not have an commissioner who was a university graduate.

In Korea, Matsuo served as the general manager of the Ulsan and then Taegu airfields before suddenly being directed to return to Japan in 1938 where he became general manager of Osaka Airfield.

Matsuo recalled keenly feeling the difficulties that can come with being in government service arising from the sudden transfer order. In any case, exchanges of personnel among these aviation authorities in the home country and territories were a fact of life.

(Mizusawa Hikari, Researcher at JACAR)

(*This essay is based on the author's own opinions and does not represent the official views of the center.)

【 Bibliography 】

- Japan Tourist Bureau, ed., Ryotei to hiyō gaisan [Itineraries and cost estimates], various years.

- Aviation Bureau at the Ministry of Communications, ed., Kōkūyōran Showa 14 nenban [General survey of aviation in 1939], 1940.

- Japan Aeronautic Association, ed. Nihon minkan kōkū shiwa [Historical anecdotes on Japanese civil aviation] Japan Aeronautic Association, 1966.

- Mizusawa Hikari, Gunyōki no tanjō: Nihongun no kōkū senryaku to gijutsu kaihatsu [The birth of the warplane: The Japanese Army’s aviation strategy and technological development], Yoshikawa kōbunkan, 2017.

![Homeland and Overseas, as Seen in Archival Records : Personnel Changes around Former Colonies and Occupied Territories [JACAR Glossary]](../../images/logo.png)